When my parents decided to defect from communist Romania in 1987, the journey started with them telling a little white lie: “We’re going on a vacation.” To my three-year-old mind that meant packing all my toys, bragging to my cousins, and being told by all my relatives that “hotel” is not pronounced “gotel.”

What I didn’t know then was that we were weren’t planning to return and that we couldn’t really tell anyone that we were leaving forever either. Once the government got word of our permanent exit, they would (and did) interrogate all our family members and punished them miserably with new work reassignments in remote areas and demotions in their work status. If the interrogators picked up on any signs that our relatives knew, and didn’t report us, the punishment-by-proxy could be far greater.

So, instead, my mother slowly gave away our nicest possessions, said we were downsizing, and made sure to spend time with her sisters before we left. One of them caught on and on the day of our vacation, she handed us a box of home baked pastries and said, “if anything goes wrong on your ‘vacation,’ eat these cookies…” Speaking in a code like this was a necessary second language in a totalitarian state. We didn’t know what the cookies would do—it was all very Alice in Wonderland sounding—but we kept note of her message.

To leave the country at all, even for a vacation in another part of the Eastern bloc, required special permission from the state. My father was a judge, a seemingly loyal citizen with no visible reason to want to defect. We were granted legal permission to visit Hungary, but my dad’s secret plan was to sneak across the iron curtain and end up in west Germany. This was a risky move with not too many safe options for passage. Some people tried to swim across bodies of water to escape and were often met with gunfire. We had to tread carefully.

People often wonder why we were willing to take this risk. Was it the ban on contraception, the syringe shortages in hospitals, the resulting spikes in HIV rates across Romania? The fact that we had to register our typewriters and unplug our phones if we wanted to have a private conversation? That our own brothers and sisters could be informants for the state? It was the great trifecta of all these things—coupled with austerity measures that left people waiting on day-long lines just to pick up a small ration of butter. Holidays went by without meat or gas for heat, icesheets formed on the windows of those infamous concrete slab buildings that housed hundreds of people. Beautiful buildings and rich history were razed to the ground—total admiration and adulation for the dictator (who greatly admired extremely totalitarian North Korean policy more than Soviet policy) was the norm.

My father, once a loyal believer in the system, had no faith in it anymore and was overwhelmed by the corruption and exploitation. My mother didn’t want to leave, but she was worried he would take me with him if she didn’t come. On the day we left for our “vacation,” we only packed a single suitcase. My mother said, “you can pick one toy, the rest will be here waiting for you.” My father hid an English dictionary in the trunk, under the car tire, should anyone search the car and suspect we were traveling traitors.

In Hungary, we dutifully did all the touristy things, just in case we were being watched. Then we stayed at various outdoor campsites and spoke in whispers to other would-be defectors. My dad was tipped off to the parts of the border that would be easiest to cross. We tried there but were denied crossing. We were also warned that our names would be sent to the Romanian government. This meant my parents would get arrested upon our return, interrogated, and possibly worse. Many were sent to arduous labor camps, and some were never heard from again. Returning was not an option.

Romania, 1985.

My mother and I in her childhood village, by the car we would later defect in.

Most nights, we slept in our car and ate hard boiled eggs. One night, we went to the dining hall of a cheap “gotel” and overheard someone talking about a safer border crossing into Austria. The next morning, we forged ahead. I remember sitting in the back seat of the car feeling the tension in the air as we approached a border again. My father was nervous, stuttering when he spoke to border patrol—something about freedom, and wanting a better chance “for her,” as he motioned to the backseat. The guard took our papers and walked away. My mother’s softly sloped shoulders were up by her ears. I fogged up the side window and drew stars on the condensation with my fingers, wishing I was anywhere but there. They came back and took my father away to question him. We waited. Finally, the guard returned with my father, whose clothes were disheveled from whatever search they put him through. The guard said he would let us cross, but only if we can pay the “car tax.” My parents took out money in various Eastern bloc currencies, none of which were viable in the western economy. The guard eyed my mother’s wedding ring as potential tax currency. But then, my father remembered the box of cookies.

He immediately started to tear through them with his teeth and fingers, cinnamon raisins flying everywhere. He chewed with haste, not pleasure (my child-mind was scandalized). He pulled out a small crumpled-up green piece of paper. He unfolded it against the dashboard, dried it against his leg, and handed it to the guard. It was a $100 USD bill – illegal currency in Romania – that my aunt had cleverly baked into the pastry. The guard took it, handed up a tax receipt, enough change for our first lunch in the West, and we were off to Vienna.

When we arrived in the capital city, where all the buildings looked like wedding dresses, my father approached a street sweeper who looked Eastern European and asked him where we should go to declare ourselves refugees. From there, we went to a giant refugee camp – a massive collection of buildings in Traiskirchen, a former cadette training ground, and began our multi-year journey as refugees. In Austria, I learned German and Polish to talk to kids my age. Those children quickly disappeared, reassigned to other countries or housing without warning. We lived in giant mess halls and slept on bunk beds across from other defecting families. My father worked in the beet fields and would come “home” with purple fingers. My mother, a former dentist, waited in a line with other mothers as Austrian women came to pick out workers for their house cleaning tasks. One woman went around asking each of them what country they were from. When my mother said Romania, she skipped past her. That was our first lesson in how whiteness is a construct, how difference is imposed as a matter of convenience for those who wield its power.

We lived in motels. We biked the countryside to get groceries. My father would sneak me into traveling circuses for entertainment. Two years into our legal limbo, my mom became pregnant—I was going to have a sister. A few months later, my sister Julia was born with a fatal chromosomal disorder. This was something that could have been tested for in the womb, but my father wanted us to keep a low profile, to avoid seeming like the type of immigrants who “take advantage” of the system. Julia died a few months after she was born. We buried her in a small silver coffin the size of a shoebox. It was the first time I saw my father cry. Nuns joined us at the burial so that our small three-person family felt a little fuller for a moment. My parents kept going to various immigration interviews, hoping to establish legal status somewhere. Denmark, South Africa, and Spain said no. Canada said they did not take communists, even former ones. America, however, finally said yes.

On November 9th, 1989, as the Berlin Wall was hammered to the ground in Germany, my parents and I were on a Pan-Am flight across the Atlantic Ocean headed for JFK airport in New York. I did not know this then, but we were sponsored by the International Rescue Committee (IRC). Now, I am a communications manager for IRC and am working on the script for an informational video about how refugees are welcomed at the airport, what role these resettlement organizations play in helping refugees make a new home after so much time in transition.

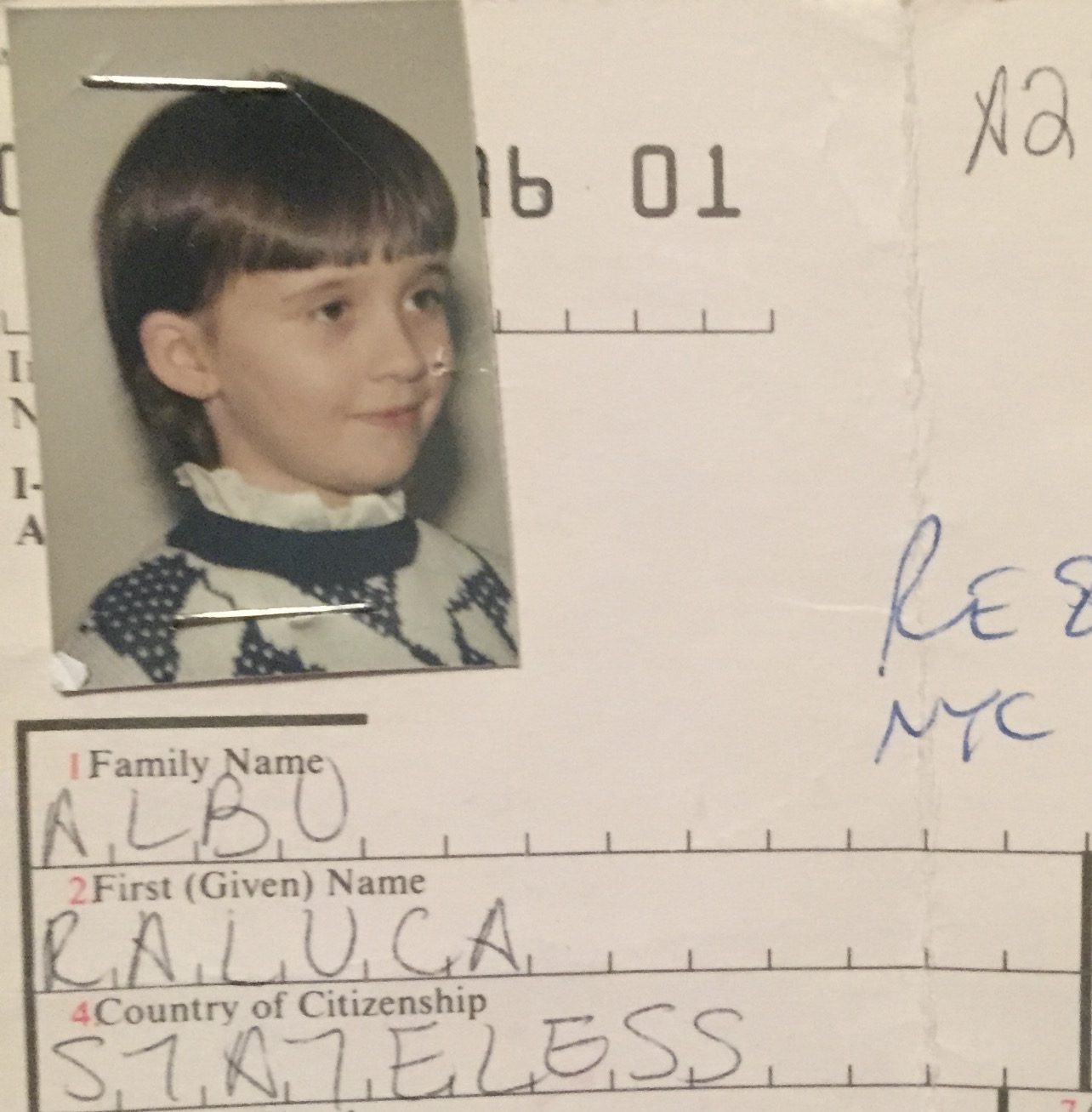

Austria, 1989.

My father’s official paperwork photo, stamped by the IRC.

A few years ago, I returned to the camp in Austria in search of my sister’s grave. We left the country hastily and were not able to purchased a tombstone. What I found when I returned was a new robust refugee community, this time from the Middle East. I befriended many of them and saw so many of the parallels within our journeys—and the differences too. While we faced some discrimination when we were there, we then moved to a country where we were dissolved into the privilege of our whiteness. Many of the new refugees were escaping war. While we were political refugees escaping an internal war of the soul, one of mistrust and control, the stakes at hand for Afghan, Iraqi, and Syrian refugees were even more staggering.

In short, that is why I do the work I do with Switchboard. I have seen the experience from both sides and know the refugee identity does not begin with the resettlement process but with an entire world of events that precedes it. The impact of those things does not go away when someone is no longer a refugee. Indeed, those years and experiences stay with us always. I asked some of my Switchboard colleagues, many who are immigrants or children of immigrants themselves, to reflect on their work on our team, and here is what they had to say.

“I did not come to the United States as a refugee myself, however, I see World Refugee Day as an opportunity to spread awareness about the millions of people who had to leave their homes forcibly. The team I work on also wants to encourage people to advocate for refugees who are working hard every day to overcome the barriers in their paths. World Refugee Day is also a chance to celebrate and share with the world the resilience and many accomplishments of refugees, which should be remembered and celebrated every day. The best part of our work is when we get to know about the impact of what we are doing. We work to see change and to support the resettlement journey of refugees coming to the United States. The best part is when we know we are in fact contributing to and supporting refugee service providers to make that change happen.”

Working for Switchboard is meaningful to me, because I know what it feels like to enter the field of refugee resettlement with a lot of passion but without experience. I love knowing that we are empowering service providers to best set their clients up for success.

I am pleased to be able to contribute my skills in digital marketing, software development, and technical support to Switchboard. World Refugee Day is an important opportunity to raise awareness of the plight of refugees and to celebrate the contributions they make to our society. I am proud to be able to play a small part in helping to improve the lives of refugees and those who work to support them

“For me, World Refugee Day is a time to acknowledge and reflect on the sacrifices and to celebrate the resilience achieved by millions of refugees worldwide, including my own family. It’s a day to honor the power, strength, success, and stability of those who sacrificed so much. It’s also a day to remember and uplift those still fighting for their safety and freedom worldwide.”

“One of the things that I appreciate about initiatives like World Refugee Day is the work put toward advocacy and raising awareness to make communities around the world more welcoming and to create comfortable environments for incoming refugees.”